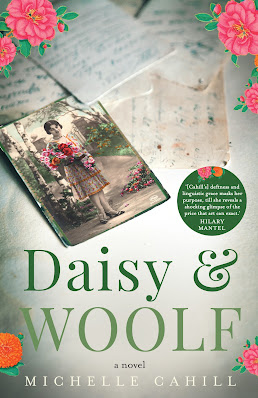

This week, I was interviewed by Kate Evans and Cassie McCullagh for Radio National's 'Bookshelf' program about Michelle Cahill's debut novel, Daisy and Woolf.

The opening premise of this book is an author's attempt to write a novel about Daisy Simmons, a minor character in Virginia Woolf's Mrs Dalloway. In the original text, Daisy is referred to only briefly through the viewpoint of Peter Walsh, her lover who is arranging her divorce from her husband. Peter is uncertain about whether he really wants to be with Daisy, and seems more concerned that she isn't with anyone else. Daisy, meanwhile, is about to give up a great deal for him: she is leaving her husband, her family and friends, and her home in India in order to marry him.

In Daisy and Woolf, we follow the efforts of Mina, an Anglo-Indian author from Australia, as she arrives in London to see whether she can discover a more complete story for Daisy than the one we get in Mrs Dalloway or has been sought in critical responses to the book. What follows is also an exploration of the potential of creative writing as a form of criticism: because creative writing is a very permissive and open form that absorbs and celebrates desire, social situations, and relationships, the interpretive act is also a representation of family, artistic aims, sex, geography and, perhaps more pointedly in this case, of the role of race and ethnicity in our lives. Mina as an author has much in common with Daisy, and thus her written work is also an attempt to define and understand a meeting between them that occurs on the page.

As well as response to the content and characters of Mrs Dalloway, Cahill's work is a tribute to the spirit of modernism, and in particular the way modernist writers experimented with form. Daisy and Woolf is a hybrid work with elements we recognise from epistolary novels, autofiction, literary criticism, writers' reflections on writing, and historiographic metafiction. Thus, while the book questions Woolf's depiction of Daisy, it is also a tribute to the boldness of Woolf's prose and modernist writing and its concern with experimentation. As a result, as I was reading, I found myself making connections with quite a wide range of works, such as The Details by Tegan Bennett Daylight, Karl Ove Knausgaard's My Struggle, Hannah Kent's Devotion, and Jack Maggs by Peter Carey. I could list others, but the point is that this book has a richly mixed heritage both culturally and formally.

The end result, I think, is a work that searches for the place of storytelling in our reception of earlier works. In this case, we see how that search might combine literary and race theory to develop an argument, or at least reflection, about the embodied, experiential nature of writing practice and interpretation.

Our discussion of this book on Radio National is available in full here.

*